“(…) The perspective of the economic and monetary union will therefore be confirmed in all its decisive significance … But just because it is a crucial fact, I think we should request that it has its natural completion in a common policy of movement and progress, that is, an initiative that is not restricted to enhancing the wealth where it is, but knows how to balance and make justice. (…). And so it is to be expected that the most depressed classes are raised, the social views are seen in their dignity, culture is widespread, youth valued in a free movement and contact, beyond the old boundaries, a European citizenship, even for a progressive implementation, recognized (…)”.

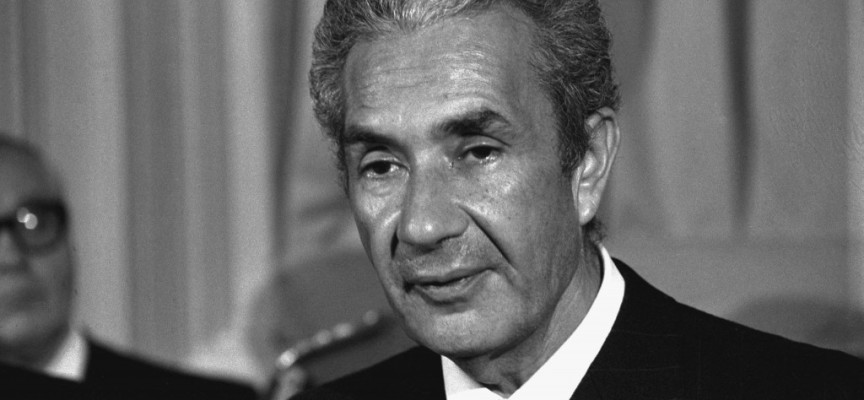

Aldo Moro wrote this in an Italian newspaper on October 15th, 1972. His expectations corresponded to the “dream” of the fathers of the European community. The answer remained largely unfinished not for the “dream” of Moro, who recalled that of the fathers of the united Europe, but for a common European policy which has failed to live up to a challenge that thirty years after was, so to speak, summarized in the single currency.

It is, however, a ground for gratitude and hope to resume Moro’s European thought 100 years after his birth (1916-2016) and three months after the start of the celebrations of the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome (25th March 1957). It is also important to remember that last February 24th, because of his look which went higher and farther, a room at the European Parliament was dedicated to the Italian statesman.

On that occasion the President of the Italian Republic, Sergio Mattarella, said: “Europe is a decisive crossroads in Aldo Moro project. He believed – as he said in his last speech in Parliament – that ‘pro-European vision’ was ‘connatural to the Italian people’ and he thought of united Europe as a factor of international balance and as an engine for cooperation, solidarity and peace. Moro talked of a political Europe when only the Economic Community existed. And the strengthening of the democratic nature of its institutions – of which the direct election of the European Parliament was the introduction – was conceived in a process of enlargement of the popular bases. The strength of an institution – this is Moro’s very relevant lesson – is strongly connected with its democratic dimension and with its ability to include”.

Moro was thinking of a strong European Parliament, democratic and representative, and with this determination he contributed to the reform which in June 1979 led to the first election of the European Parliament by universal suffrage. The murderers of the Red Brigades also prevented him to see this milestone.

European integration proceeded anyway even if not always in the spirit of the founding fathers and today, in a time when “Europe knows difficulties and troubles in the face of economic crisis, financial instability, migrations, wars that are fought in the Mediterranean and in the Middle East, the large imbalances in wealth and opportunity” it remains, in line with Moro’s thought, “a historical task”.

The Italian statesman thought Europe not as an “autarchic entity” but “a union open to international collaboration” and thus the strengthening of the integration intended by the founding fathers would have had to strengthen the awareness of the international mission of the European Community.

It was the political wisdom which today we miss with concern in a world torn apart by wars led from sick powers and where the European Union is absent. Until when?

On another front the topicality of Moro’s European thought is revealed: the Mediterranean.

Turned into a large cemetery in the moonlight and in a space where the “de facto solidarity” succumbs to the selfishness of the single European countries, the Mediterranean stands as a symbolic place where to start to build hope and trust. A place, Aldo Moro would say, from where to shake and awaken European conscience. Perhaps starting with the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Treaties of Rome.

“(…) La prospettiva dell’unione economica e monetaria sarà dunque confermata in tutto il suo determinante significato… Ma proprio perché si tratta di un fatto decisivo, penso che noi dovremmo chiedere che esso abbia il suo naturale complemento in una politica comune di movimento e di progresso, cioè un’iniziativa che non si limiti a potenziare la ricchezza dov’è, ma sappia equilibrare e fare giustizia (…). E così è da attendere che i ceti più depressi siano sollevati, le parti sociali viste nella loro dignità, la cultura diffusa, la gioventù valorizzata in un libero movimento e contatto, al di là degli antichi confini, una cittadinanza europea, sia pure per una graduale attuazione, riconosciuta (…)”.

Così scriveva Aldo Moro su un giornale italiano il 15 ottobre 1972. La sua attesa corrispondeva al “sogno” dei padri della comunità europea. La risposta è rimasta in buona parte incompiuta non per il “sogno” di Moro, che si richiamava a quello dei padri dell’Europa unita, ma per una politica comune europea che non ha saputo essere all’altezza di una sfida che trenta anni dopo veniva, per così dire, riassunta nella moneta unica.

È tuttavia motivo di riconoscenza e di speranza riprendere il pensiero europeista di Moro a 100 anni dalla nascita (1916-2016) e a tre mesi dall’inizio delle celebrazioni del 60° anniversario dei Trattati di Roma (25 marzo 1957). È altrettanto significativo ricordare che lo scorso 24 febbraio, proprio per il suo guardare più in alto e più lontano è stata dedicata allo statista italiano una sala nella sede del Parlamento europeo.

In quell’occasione il presidente della Repubblica italiana, Sergio Mattarella, ebbe a dire: “L’Europa rappresenta un crocevia decisivo nel disegno di Aldo Moro. Riteneva – come disse nel suo ultimo intervento alla Camera – che ‘la visione europeista’ fosse ‘connaturale al popolo italiano’ e pensava all’Europa unita come fattore di equilibrio internazionale e come motore di cooperazione, di solidarietà, di pace. Moro parlava di Europa politica quando era ancora presente soltanto la Comunità economica. E il potenziamento del carattere democratico delle sue istituzioni – di cui l’elezione diretta del Parlamento Europeo è stata premessa – era concepito dentro un processo di allargamento delle basi popolari. La forza di un’istituzione – questa è una lezione attualissima di Moro – è fortemente connessa con la sua dimensione democratica e con la sua capacità d’inclusione”.

Moro pensava a un Parlamento Europeo forte, democratico e rappresentativo, e con questa determinazione contribuì alla riforma che nel giugno 1979 portò alla prima elezione del parlamento europeo a suffragio universale. Gli assassini delle Brigate Rosse gli impedirono anche di vedere questo traguardo.

L’integrazione europea procedette comunque anche se non sempre nello spirito dei padri fondatori e oggi, in un tempo in cui “l’Europa conosce difficoltà e affanni di fronte alle crisi economiche, all’instabilità finanziaria, alle migrazioni, alle guerre che si combattono nel Mediterraneo e nel Medio Oriente, ai forti squilibri nelle ricchezze e nelle opportunità” rimane, in coerenza con il pensiero di Moro, “un compito storico”.

Lo statista italiano pensava l’Europa non come “un’entità autarchica” ma “un’unione aperta alla collaborazione internazionale” e quindi il rafforzamento dell’integrazione pensata dai padri fondatori avrebbe dovuto rafforzare la coscienza del compito internazionale della Comunità europea.

Era la saggezza politica di cui oggi si avverte con inquietudine la mancanza in un mondo dilaniato da guerre guidate da poteri malati e dove l’Unione europea è assente. Fino a quando lo sarà?

Su un altro fronte si rivela l’attualità del pensiero europeista di Moro: il Mediterraneo.

Trasformato in un grande cimitero sotto la luna e in uno spazio dove la “solidarietà di fatto” soccombe all’egoismo di singoli Paesi europei, il Mediterraneo si pone come un luogo simbolo da dove ripartire per costruire speranza e fiducia. Un luogo, direbbe Aldo Moro, da dove scuotere e risvegliare la coscienza europea. Magari a partire dalla celebrazione del 60° anniversario dei Trattati di Roma.

Paolo Bustaffa

Latest posts by Paolo Bustaffa (see all)

- Europe in Aldo Moro’s project - 31 dicembre 2016

- Ventotene: a cultural alliance between generations is urgent for the EU - 3 settembre 2016

- That flag in the Wyd - 7 agosto 2016